I haven’t done a complete literature review yet (will take a

while), but as far as I can tell, there are two things the human

wellbeing/happiness literature hasn’t really tackled yet:

1. Moving beyond happiness and subjective wellbeing

to a more comprehensive model of human flourishing (e.g. happiness + meaning +

needs) that can be estimated using a regression. A regression would allow you

to weight the variables that affect human happiness appropriately. I foresee

many problems; the most obvious is that some things are obviously non-linear,

like the impact of income.

2. Examining both preference and life outcomes.

There is plenty of literature looking at the effect of preferences on

happiness, and plenty of literature on the effect of life circumstances on

happiness. But, as far as I can tell, nobody has put the two together yet.

I addressed the first issue somewhat in my last article, so

I won’t dwell on it here. I will be working on a collaborative project tackling

it throughout this year, so I’ll post plenty of thoughts in the coming weeks.

Why do we need preferences and life circumstances? I have

two main reasons. First, the philosophical literature basically says that it is

the affirmation of preferences that leads to human flourishing. Preferences

will contest with each other in the mind of the individual, but in the long

run, living in accordance with the preferences that win out will lead to you

enjoying your life.

Second, different things make different people happy. I

recently read some literature on how materialistic preferences are less likely

(not much) on average (never forget that caveat) to result in happy people.

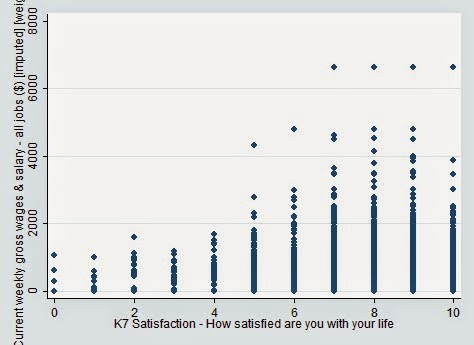

However, if you plot wages against life satisfaction for people who answer

9/10+ to “how important is financial security to you” using the HILDA data, you

get the following graph.

There is clearly a positive correlation. Indeed, it looks

exponential until the plateau around 8 and then a slight dip, in line with most

of our theory on these things. So the materialism preference is only dangerous

if one cannot affirm it. I suspect preferences for community would be equally disastrous to happiness if individuals were unable to affirm them.

So we need to analyse preferences and life circumstances together. We could take one as exogenous and endogenise the other and vice versa, Perhaps there might even be a way to do them together. We'll see.

The key issue with empirically investigating these issues

further at this stage is that we don’t have good data on preferences. There are

small studies but they have bad samples, limited data on life circumstances and

usually no repeated observations. HILDA, the set I work with the most, has data

on some preferences—for religion, community, financial security, leisure and

some others. That’s a start, but a very limited one.

A second, though arguably no less critical issue is that the

preference data usually comes in the form of a bounded variable operating

between 1 and 10 i.e. “on a scale of 1-10, how important is x to you?”. The

problem here is that there are no trade-offs. There is no reason why someone

can’t have a 10/10 preference for financial security and a 10/10 preference for

leisure, even though in practice there is likely to be a trade-off between the

two. We need someone to get at trade-offs and develop a marginal rate of

substitution curve.

A tertiary issue specific to these variables in the HILDA data set is that they only occur in the first wave of the panel, which extends for 12 years. You can use lagged variables, but in my experience mucking about with these variables, you can get quick different results depending on which wave you are looking at. Panel data techniques would help except they are under-identified because you have 12 years of life data but only 1 year of preference data.

A tertiary issue specific to these variables in the HILDA data set is that they only occur in the first wave of the panel, which extends for 12 years. You can use lagged variables, but in my experience mucking about with these variables, you can get quick different results depending on which wave you are looking at. Panel data techniques would help except they are under-identified because you have 12 years of life data but only 1 year of preference data.

In the long run, what I would like to do is infer some

trade-off style preferences from the data. HILDA is rich enough to allow us to

identify where someone begins to trade-off between, say, more income from work and

more leisure time. This is an emerging literature in econometrics, so it will probably

be hard going, but I think it has a lot of promise for getting us a more

meaningful analysis of human flourishing.

Comments

Post a Comment