I have watched with mounting despair the recent turn among American economists to reconsider the costs and benefits of free trade. Much of this is driven by the empirical work of Autor on the China shock to US manufacturing. Most recently, David Dorn and Peter Levell wrote a piece for Vox arguing, based on an analysis of the US and UK experiences, that trade might perhaps increase inequality, contra traditional economic theory. Noah Smith tweeted it out with the caption “Trade with China was what destroyed the pro-free trade consensus among economists”. I watch this with despair because in East Asia (and pretty much everywhere but the UK and US), free trade with China has been meaningless for inequality, and good for pretty much every other economic indicator we might care about, including in already developed nations, including those that have always had substantial manufacturing industries, like South Korea and Japan. The key difference between these countries and the US is how they compensate the losers from trade by redistributing the gains from winners. The US and UK don’t do this well because they undertook trade liberalisation under the neoliberal administrations of Reagan and Thatcher, who couldn’t give a f**k about equality. Trade isn’t the issue. US and UK policy settings beyond trade are. Allow me to explain.

Let’s start with a brief recap of

microeconomics 101. The theory of comparative advantage demonstrates rather compellingly

that if nations specialise in those things they can produce at lowest

opportunity cost and trade they are all better off. I won’t go through the 2x2

matrix model of this fundamental insight of economics. Marginal revolution university

does a great job of it

here.

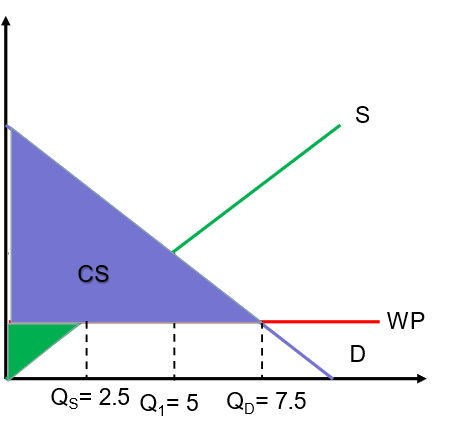

When we model gains from trade from liberalisation

to imports and exports, we see that there is a net benefit, but the gains are

unevenly distributed. Some parts of the market gain while others lose. Below

are the graphs for imports, where consumer surplus grows at the cost of

producer surplus, and exports, where producer surplus grows at the expense of

consumer surplus. In both cases, there is a large gain in total economic

activity as a result of being open to international markets.

Now often these basic microeconomic graphs are too neat for reality. Minimum wage theory, for example, has taken something of a beating lately in the empirical literature. Is it the same for trade? I daresay no, but it depends where you look. In the US and UK, China’s entry into the world trading system from the late 1970s onwards decimated the manufacturing and heavy industry hubs, notably in terms of job losses and reduced wages, and many associated towns never recovered. Trade must suck then right? No.

In Australia, China sent cheap manufactured

goods, and Australia sent back raw material and some services. This was

facilitated by a wave of liberalising reforms in Australia in the 1980s that almost

completely opened the country to all foreign flows: goods, investment,

currency, etc. This was very similar to the liberalisations in the US and UK. A

key difference, one mirrored in most EU nations, was that alongside market-oriented

reforms there were also substantial social reforms. Notably, public involvement

in health, education, infrastructure, and the labour market (especially through

active labour market policies like retraining and unemployment insurance) grew

markedly. Not necessarily in a ‘big government’ kind of way, more in a market

facilitating kind of way. But the key thing was people weren’t just left to

fend for themselves against market forces.

Let’s look at two key examples of such

policies. In Australia, most students finance their tertiary education fees through

income-contingent loans made directly by government, not banks with government

acting as guarantor. We see here both a price signal and government acting as insurer

– comparative advantages of the market and state respectively. This approach keeps

interest rates at a minimum rather than a profit-maximising level (for private

banks!). It also means that students only have to pay back their loans once

they earn an income at the 5th decile of household income, so there

is no loans stress like in the US (and now the UK since they ‘reformed’ their

system under Cameron). This system makes education and retraining much more accessible for people of limited means that the US approach.

In Denmark, the flexicurity system means that workers

pay a small levy while working (that they would not in a 'low tax' 'small government' country), but then receive close to replacement wages for

the first 6 months while they are unemployed. They then revert to breadline

levels of payments. This allows them to keep making mortgage repayments and

otherwise living their life while they find a new job or retrain. In contrast,

the stingy approach to unemployment payments in the US and UK keeps workers a

paycheck away from poverty and massively reduces their bargaining power with

employers. Danes are also entitled to claim welfare payments while retraining, which

facilitates regular skills upgrading. This prevents them becoming obsolete the

way US and UK workers did. The Danish government coordinates regular

conferences and negotiations between unions, business groups, and education

providers to ensure workers retrain in needed skills and are properly

compensated for the associated costs. Finally, Denmark uses a ‘good faith’ approach

to industrial bargaining, which means that bosses must release their books to

unions. In this way, the marginal contributions of capital and labour can be

easily calculated, and negotiations take place over the surplus. In the US and

UK, in contrast, labour regulations strongly favour bosses.

These sorts of policies are tax-financed in

progressive ways, ensuring, in a broad way, that those who benefit from trade

compensate those who lose. Denmark and Australia have experienced sustained growth,

consistently low unemployment (despite high migration), and barely any increase

in post-tax-and-transfer inequality in the past four decades. Note that none of

these policies has anything explicitly to do with trade. They just ensure that

trade works. If you analyse the effects of trade without considering these

contextual elements of the political-economic policies and institutions of a

nation, you will get a distorted view.

(This is a general problem for economics right

now that I want to write a separate blog about. The obsession with quasi-experimental

research methods of late means that very few economics think systematically,

nor can they offer commentary on system design, only on causal mechanisms. This

was a major part of the debate over RCTs in development – Africa has heaps of

RCTs and yet barely seems to be growing, while East Asia pursues a comprehensive

pro-growth policy agenda that is difficult to evaluate but is logically

consistent and clearly shows results).

Now you might think that Australia and Denmark

are bad comparisons because they never had big manufacturing sectors the way

the US and UK did. But then take a look at South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. All

three dramatically liberalised to trade after the WTO came into existence, and

all three have highly symbiotic relationships with Chinese manufacturing. They

each specialise in their comparative advantage in relatively high-tech,

high-value added aspects of the value chain (e.g. engineering, or

building the machines that are then put into factories). Meanwhile, China

specialises in the low tech parts, like putting the chips from Taiwan into the

plastic phone cases from China. Everybody benefits! Again, there has been low unemployment,

low growth in inequality, and high wage growth in these countries over the

past four decades. And manufacturing remains a substantial portion of the

economy. In all three countries, the government is substantially involved in education,

health, infrastructure, and labour market provisioning.

The reason why trade led to greater inequality

in the US and UK was that these countries were already iniquitous, in

particular in terms of the power that bosses had relative to workers. So when

trade liberalisation took place, workers weren’t taken into consideration much.

Most of the US trade literature focusses on how workers benefitted in terms of

lower prices for consumer goods. The real gains come from a larger tax base to

finance social mobility investments from government, but these don’t happen in

neoliberal regimes.

There is a general tendency to misunderstand

trade among US and UK economists because they draw too heavily on the Atlantic

experience and miss the East Asian experience. Trade and open economics more

broadly is the defining feature of East Asia and the key to several generations

of broad based growth in the region.

Nice one, Mark "RCT Killer" Fabian

ReplyDelete